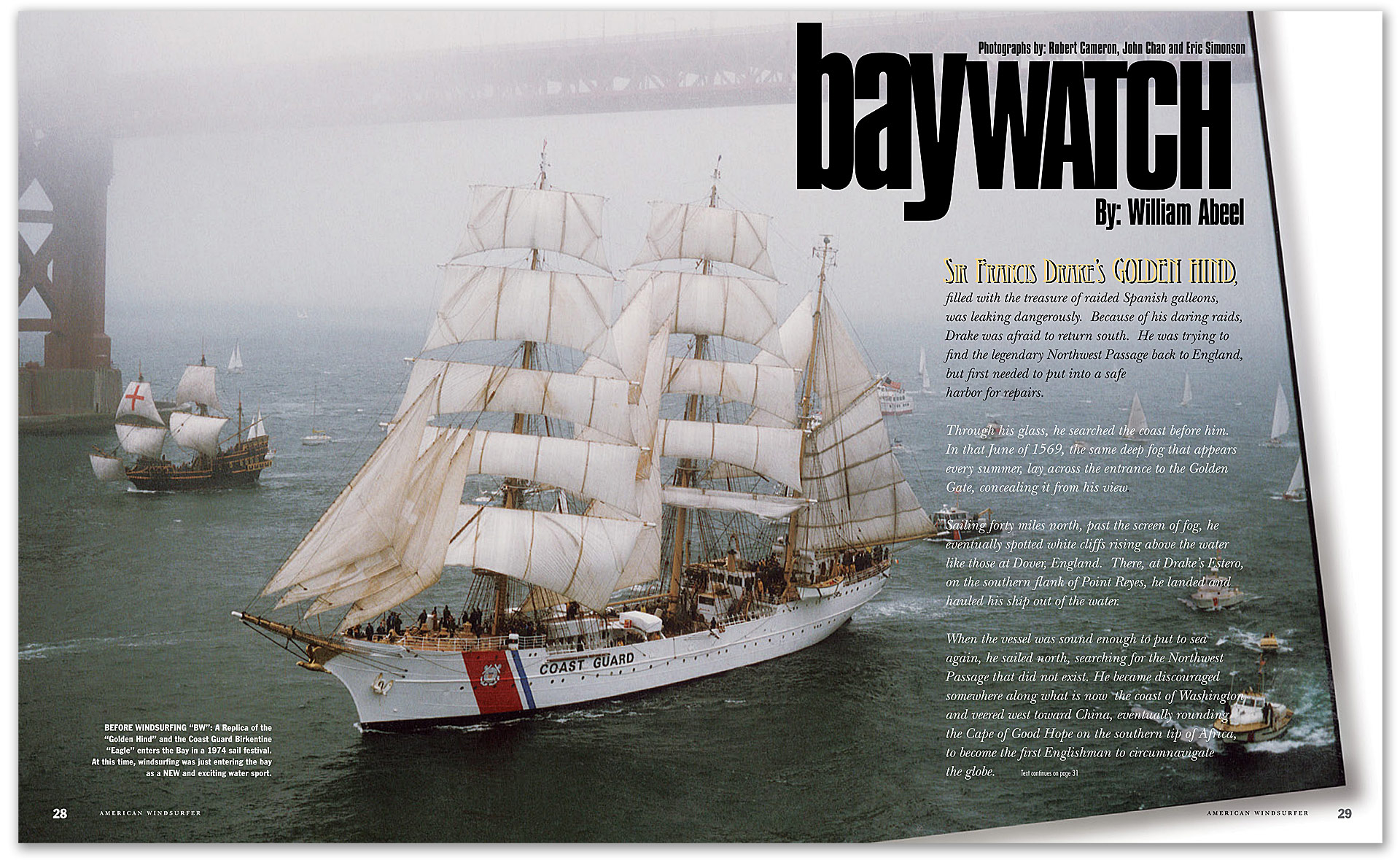

Sir Francis Drake’s GOLDEN HIND, filled with the treasure of raided Spanish galleons, was leaking dangerously. Because of his daring raids, Drake was afraid to return south. He was trying to find the legendary Northwest Passage back to England, but first needed to put into a safe harbor for repairs.

THROUGH HIS GLASS, he searched the coast before him. In that June of 1569, the same deep fog that appears every summer, lay across the entrance to the Golden Gate, concealing it from his view.

Sailing forty miles north, past the screen of fog, he eventually spotted white cliffs rising above the water like those at Dover, England. There, at Drake’s Estero, on the southern flank of Point Reyes, he landed and hauled his ship out of the water.

When the vessel was sound enough to put to sea again, he sailed north, searching for the Northwest Passage that did not exist. He became discouraged somewhere along what is now the coast of Washington and veered west toward China, eventually rounding the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, to become the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe.

Advertisement

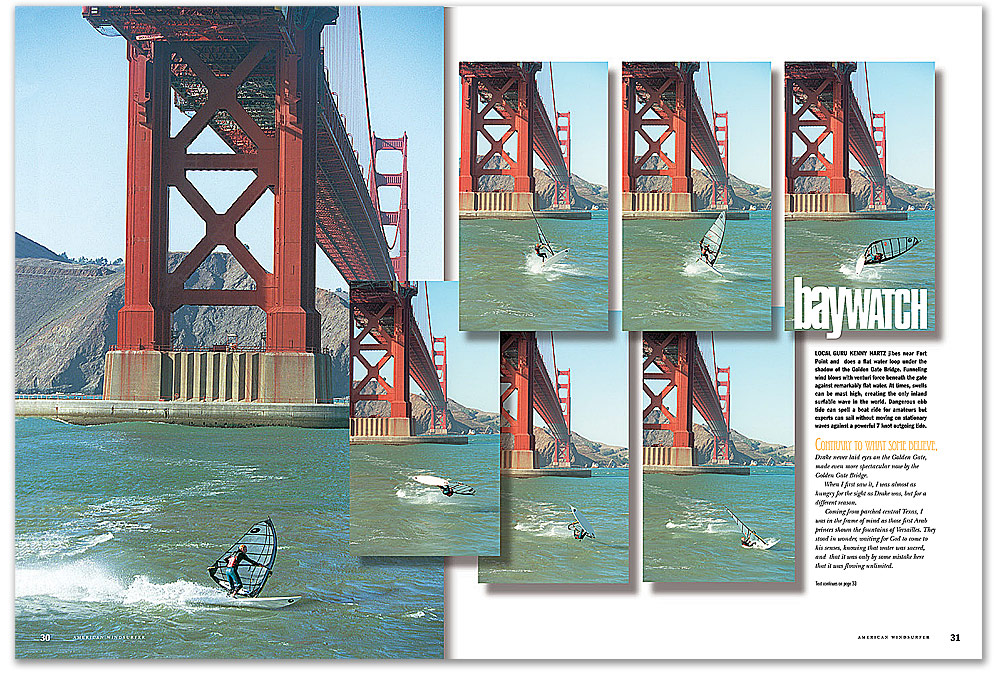

CONTRARY YO WHAT SOME BELIEVE, Drake never laid eyes on the Golden Gate, made even more spectacular now by the Golden Gate Bridge.

When I first saw it, I was almost as hungry for the sight as Drake was, but for a different reason. Coming from parched central Texas, I was in the frame of mind as those first Arab princes shown the fountains of Versailles. They stood in wonder, waiting for God to come to his senses, knowing that water was sacred, and that it was only by some mistake here that it was flowing unlimited.

Then I gaze far across at the other side and consider the 350 feet of cold water straight down under the Bridge. When I finally stand, knee-deep in my wetsuit, hands gripping the boom, back foot tensed for the right wave, I feel like Sir Frances Drake setting his sail for an unknown world.NOW WHEN I CROUCH, rigging on the beach that Drake missed, I glance up at the bridge, gauge the wind speed, check the chop and an ebbtide going out toward that same China, faster than a man can walk. Each time, I’m struck with wonder. I marvel at its beauty and my good fortune to be there. I reflect on the sanctity of abundant water and, like those first Arab princes, of people who will never see a sight like this. I think of “the Great Drought” of 1933 that started a veritable migration to this coast. I see in my mind, the scorched plains, and remember the dust storms that turn air black for a hundred miles. I also picture in my mind the stretched–out dead cattle and, looking out before me, remind myself that all life came originally from the sea.

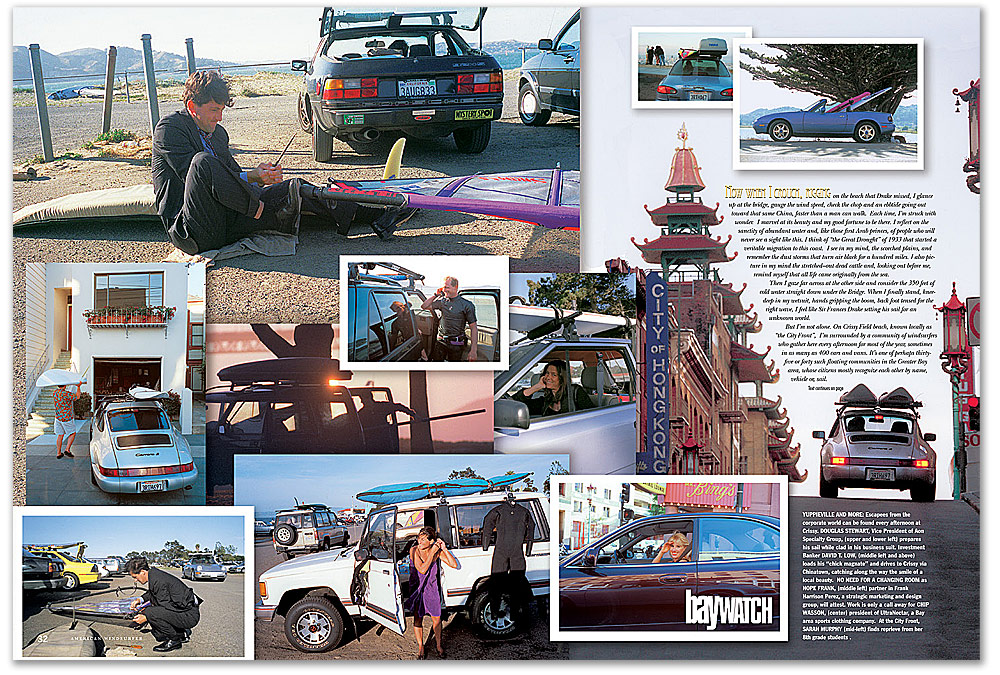

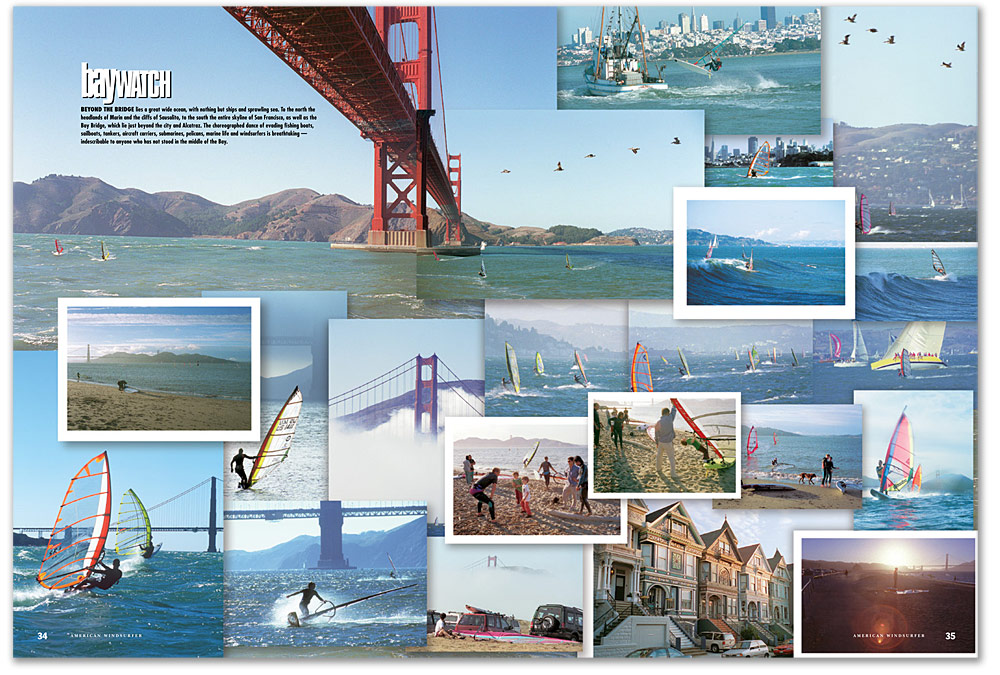

But I’m not alone. On Crissy Field beach, known locally as “the City Front”, I’m surrounded by a community of windsurfers who gather here every afternoon for most of the year, sometimes in as many as 400 cars and vans. It’s one of perhaps thirty-five or forty such floating communities in the Greater Bay area, whose citizens mostly recognize each other by name, vehicle or, sail.

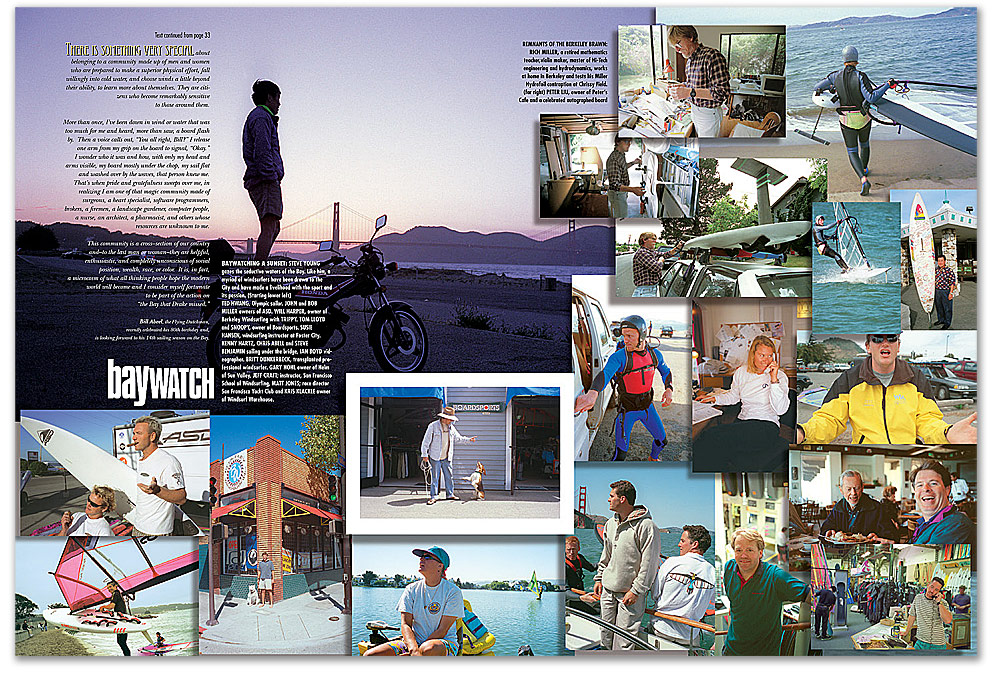

THERE IS SOMETHING VERY SPECIAL about belonging to a community made up of men and women who are prepared to make a superior physical effort, fall willingly into cold water, and choose winds a little beyond their ability, to learn more about themselves. They are citizens who become remarkably sensitive to those around them.

More than once, I’ve been down in wind or water that was too much for me and heard, more than saw, a board flash by. Then a voice calls out, “You all right, Bill?” I release one arm from my grip on the board to signal, “Okay.”

Advertisement

I wonder who it was and how, with only my head and arms visible, my board mostly under the chop, my sail flat and washed over by the waves, that person knew me. That’s when pride and gratefulness sweeps over me, in realizing I am one of that magic community made of surgeons, a heart specialist, software programmers, brokers, a firemen, a landscape gardener, computer people, a nurse, an architect, a pharmacist, and others whose resources are unknown to me.

This community is a cross–section of our country and–to the last man or woman–they are helpful, enthusiastic, and completely unconscious of social position, wealth, race, or color. It is, in fact, a microcosm of what all thinking people hope the modern world will become and I consider myself fortunate to be part of the action on “the Bay that Drake missed.”