THE FESTIVAL

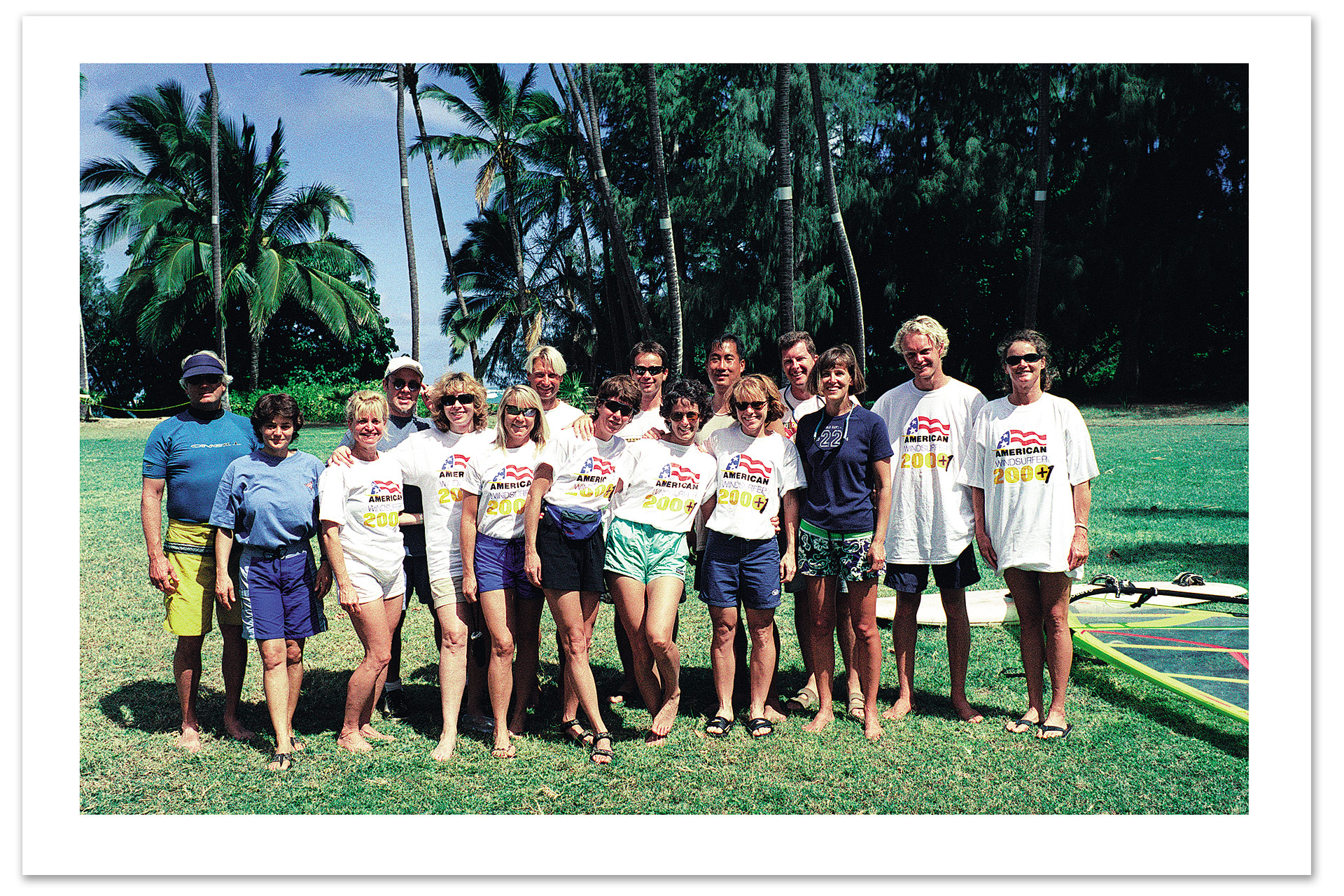

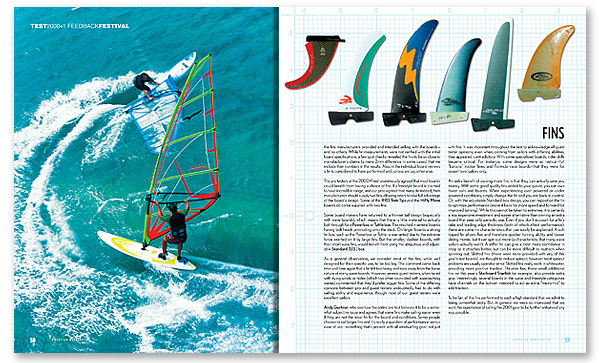

This year’s equipment test was quickly dubbed the 2000+1 Feedback/Festival as we set ourselves the goal of providing detailed equipment feedback, together with lifestyle coverage of the many people involved. The more than five weeks that the test team spent in Maui were aimed at creating something different, something never seen in the U.S. before: a windsurfing equipment test that provides truly independent results.

And we were determined to have fun doing it.

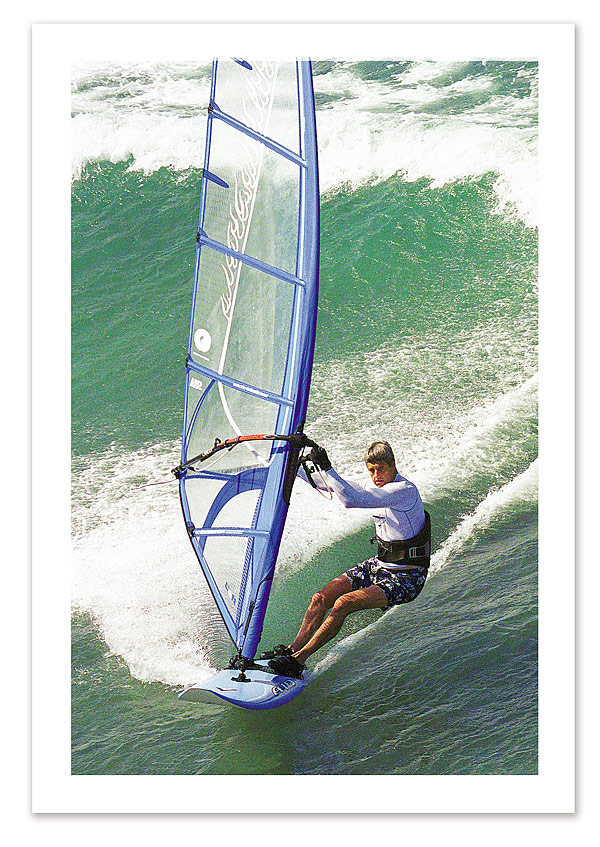

Joining us for our extended month in the sun were many guest testers. They, together with the many pro sailors, board shapers, and sail designers who turned up at the Club Paradise test site on Maui’s north shore, helped to make this a memorable test and a wonderful festival celebrating the sport and lifestyle of windsurfing. The wind blew, and at times blew strong (mental note: need more small sails next year) and the reef just off shore looked like white water rapids to the horizon. Alternatively, when the Kona winds blew in from the other direction it was hard to tell there was even a reef out there, as the waters appeared calm and placid. We had very few days like that.

Most of the guest testers, staff testers, and pros spent more days than they dared dream about ripping it up on the water. On land the pace was sometimes just as frantic. We took a pre-dawn trip 10,000 feet up the Haleakala volcano to see the sunrise, celebrated birthdays as they occurred, went surfing on the southern side of the island, and dressed up for the annual Lahaina Halloween street party. Much of the excitement and activity of the festival has been documented in words and pictures on the AW website and in the last issue of AW (8/1). Further proof that we had a ball creating this test, while not dropping the ball when it came to the results, is included in these pages.

THE FEEDBACK

We believe this equipment test is unprecedented in that no windsurfing magazine at any time in America has produced as useful an equipment test as this one, and that includes AW. This may seem like a bold statement, but as this issue of American Windsurfer Magazine goes to print, we have received praise and unexpected interest in our test from international windsurfing groups. They have assured us that we have created something new.

Indeed, when we look at others’ tests, many are not what we’d like to see. There are equipment reviews disguised as tests, glossy coverage designed to give the impression that an independent evaluation has been performed, and some simply re-state the manufacturers’ brochures. In order to be taken seriously, an equipment test must contain independent evaluations with the freedom to praise and to criticize as required. American Windsurfer Magazine has provided just such an opportunity with this year’s test.

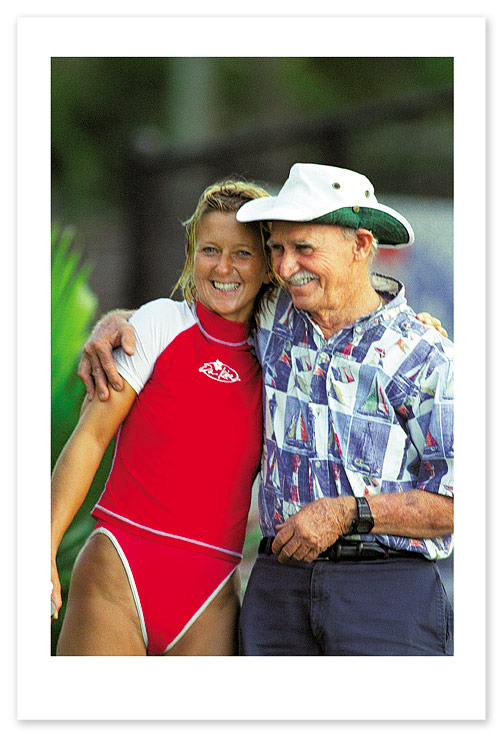

AW editor and publisher John Chao, while instrumental in financing the test and providing the magazine for which the test is named, did not determine the test format. Instead, professional windsurfer Andy Gurtner agreed to lead this year’s test team. One of Andy’s goals was to assemble a group of full time windsurfers—both men and, for the first time ever, women—to give thorough and professional feedback useful to the windsurfers of both genders, at all skill levels, as well as the windsurfing industry.

Advertisement

THE PROFESSIONAL TEST TEAM

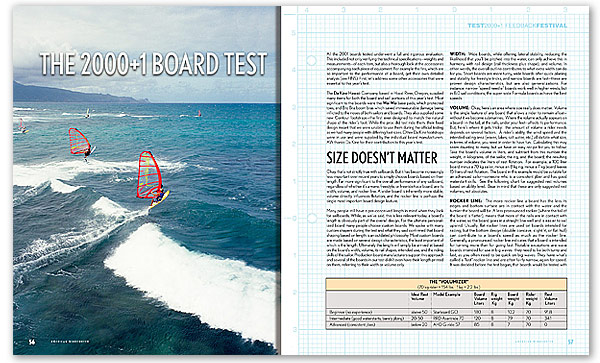

This year’s test included a well organized protest; okay, that should read Pro Test. Five professional level windsurfers gathered together on Maui’s north shore to rip, and record what they thought of the latest and best 2001 boards and sails.

Working individually, every team member tested each board and each sail within a particular category in identical conditions. For example, when testing wave boards, each pro tester worked within strict time limits to ensure equal time for each board. Each tester chose a sail and kept it throughout the day’s testing; this ensured that any performance differences could not be attributed to a new sail entering the equation. Likewise, each sail was tested using the same boom—Chinook’s new 2001 Carbon boom—and the same board. During the testing period, rapid-fire exchanges took place right on the beach. As one pro came, in another was waiting and ready to go. Immediately after each test ride, the team members completed individual reviews of the item they had just used. When it was too late in the day to test any more gear the team gathered to discuss their findings and create the group comments that are included in this report. They took pains to create as accurate and concise an opinion as possible, often working late into the night.

MEET THE TEAM

Andy Gurtner headed up this year’s pro team. He has been an instructor of windsurfing instructors for fifteen years and helped to establish the rules governing instruction for European organizations. In 1999 he moved his school from Switzerland to the Gorge.

Royn Bartholdi sails twelve months a year and competed in the Gorge Games. He sails six months of the year at the many expert level Gorge spots and six months in Maui waves. As a fulltime windsurfer, he spends more time on the water than on land.

Pascal Brönnimann competes as a pro level wave sailor and has made Oahu, Hawaii, his home for the past four years. He sails the extreme conditions at Diamond Head and Backyards and teaches surfing and windsurfing from beginner level to expert.

Claudia Grögor lives and sails in Tarifa, Spain—another consistently windy place. When not windsurfing, she works as a dentist in the town of Tarifa. Originally from Munich, she was trained as a dentist and as a windsurfer in her native country.

Hedy Gurtner is a licensed windsurfing instructor and pro level sailor from Switzerland. She now owns and operates a windsurfing business in the Gorge. Her natural athletic abilities have kept her involved in professional sports for most of her life.

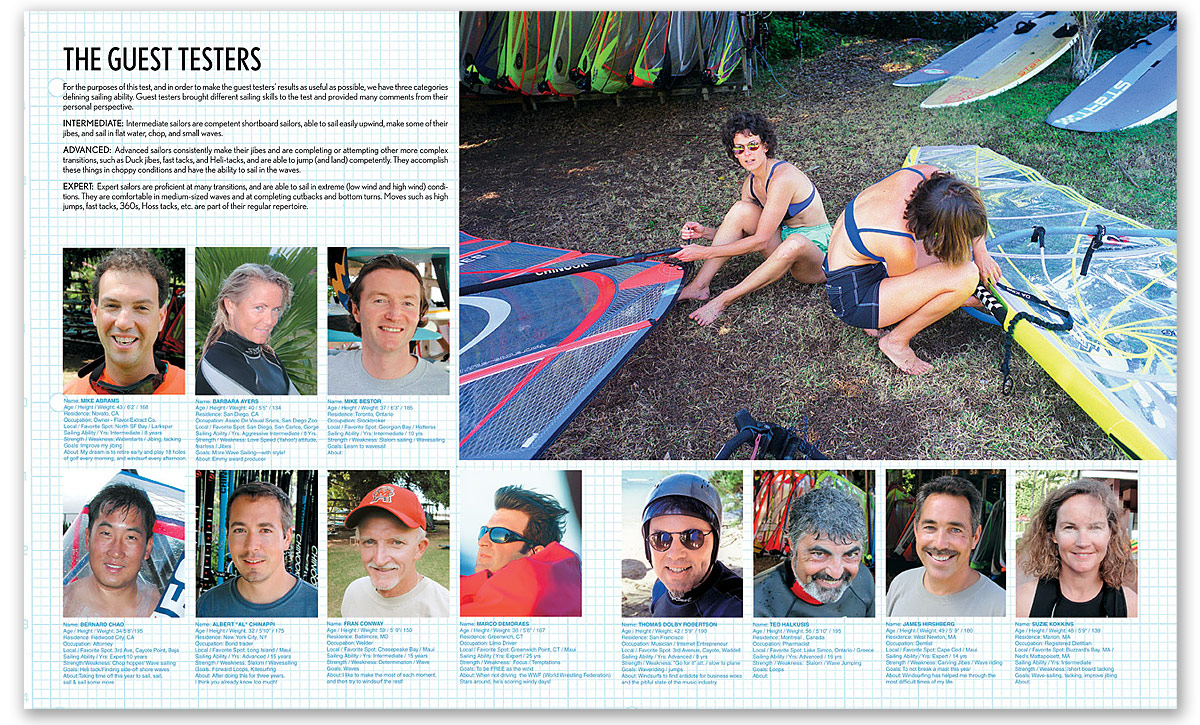

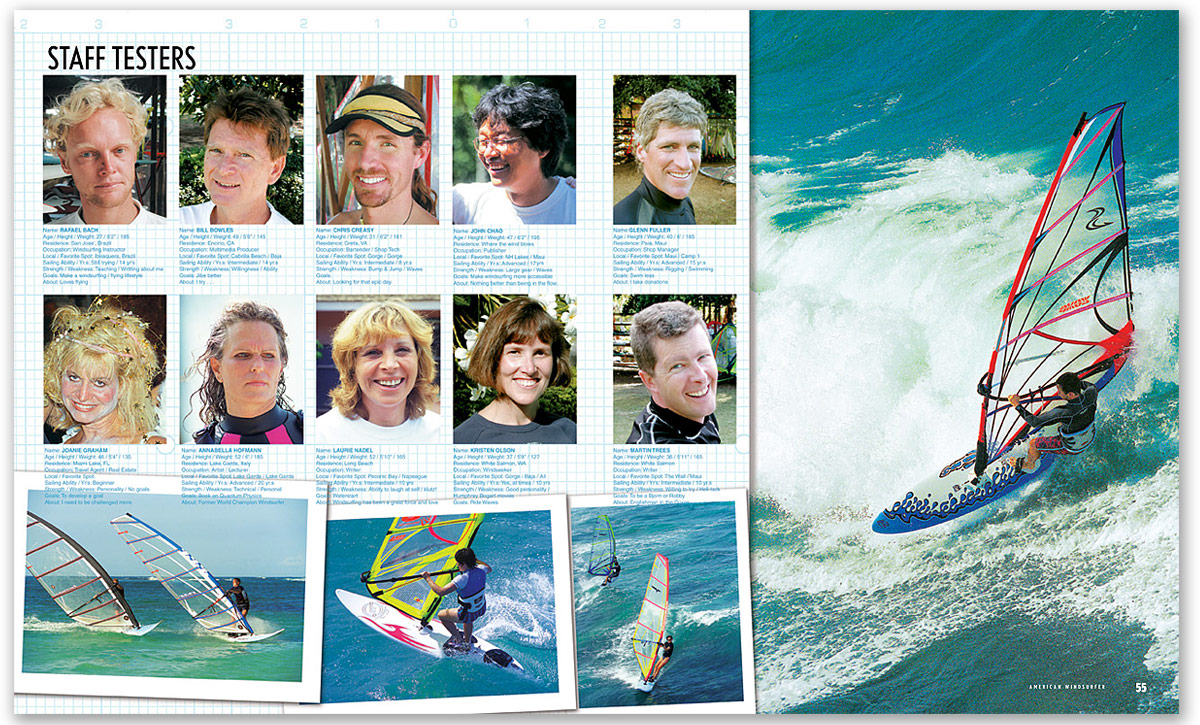

THE GUEST TESTERS

For the purposes of this test, and in order to make the guest testers’ results as useful as possible, we have three categories defining sailing ability. Guest testers brought different sailing skills to the test and provided many comments from their personal perspective.

Intermediate: Intermediate sailors are competent shortboard sailors, able to sail easily upwind, make some of their jibes, and sail in flat water, chop, and small waves.

Advanced: Advanced sailors consistently make their jibes and are completing or attempting other more complex transitions, such as Duck jibes, fast tacks, and Heli-tacks, and are able to jump (and land) competently. They accomplish these things in choppy conditions and have the ability to sail in the waves.

Expert: Expert sailors are proficient at many transitions, and are able to sail in extreme (low wind and high wind) conditions. They are comfortable in medium-sized waves and at completing cutbacks and bottom turns. Moves such as high jumps, fast tacks, 360s, Hoss tacks, etc. are part of their regular repertoire.

ALL THE 2001 BOARDS TESTED underwent a full and rigorous evaluation. This included not only verifying the technical specifications—weights and measurements—of each item, but also a thorough look at the accessories accompanying each piece of equipment. For example the fins, which are so important to the performance of a board, get their own detailed analysis (see FINS). First, let’s address some other accessories that were essential to this year’s test.

The Da Kine Hawaii Company, based in Hood River, Oregon, supplied many items for both the board and sail portions of this year’s test. Most significant to the boards were the Wai Wai base pads, which protected toes, and Bro Bra boom bras which saved immeasurable damage being inflicted to the noses of both sailors and boards. They also supplied some new Contour footstraps—the first ever designed to match the natural shape of the rider’s foot. While the pros did test ride them, their fixed design meant that we were unable to use them during the official testing as we had many people with differing foot sizes. Other Da Kine footstraps were in use and were supplied by the individual board manufacturers. AW thanks Da Kine for their contribution to this year’s test.

SIZE DOESN’T MATTER

Okay, that’s not strictly true with sailboards. But it has become increasingly less important over recent years to simply choose boards based on their length. Far more significant to the overall performance of any sailboard, regardless of whether it’s a wave, freestyle, or freeride/race board, are its width, volume, and rocker line. A wider board is inherently more stable; volume directly influences flotation; and the rocker line is perhaps the single most important board design feature.

Many people still have a pre-conceived length in mind when they look for sailboards. While, as we’ve said, this is less relevant today, a board’s length is obviously part of the overall design. For the ultimate personalized board many people choose custom boards. We spoke with many custom shapers during the test and what they said confirmed that board shaping based on length is an outdated philosophy. Most custom boards are made based on several design characteristics, the least important of which is the length. Ultimately the length will simply be arrived at based on the board’s width, volume, its rail shapes, intended use, and the riding skills of the sailor. Production board manufacturers support this approach and several of the boards in our test didn’t even have their length printed on them, referring to their width or volume only.

Width: Wide boards, while offering lateral stability, reducing the likelihood that you’ll be pitched into the water, can only achieve this in harmony with rail design (rail thickness plus shape), and volume. In other words, the overall outline contributes to what extra width can do for you. Short boards are more turny, wide boards offer quick planing and stability for freestyle tricks, and narrow boards are fast—these are proven design characteristics, but are also generalizations. For instance, narrow “speed needle” boards work well in higher winds, but in 8.0 sail conditions, the super wide Formula boards achieve the best speeds.

Volume: Okay, here’s an area where size really does matter. Volume is the single feature of any board that allows a rider to remain afloat—without it we become submarines. Where the volume actually appears on a board—in the tail, at the rails, under your feet—affects its performance. But, here’s where it gets tricky: the amount of volume a rider needs depends on several factors. A rider’s ability, the wind speed and the intended sailing area (waves, lakes, salt water, etc.) all dictate what size, in terms of volume, you need in order to have fun. Calculating this may seem daunting to many, but we have an easy recipe for you to follow: Take the board’s volume in liters, and subtract from this number the weight, in kilograms, of the sailor, the rig, and the board; the resulting number indicates the liters of rest flotation. For example, a 100 liter board minus a 70 kg sailor, minus an 8 kg rig, minus a 7 kg board leaves 15 liters of rest flotation. The board in this example would be suitable for an advanced sailor—someone who is a consistent jiber and has good waterstart skills. See the following chart for suggested rest volumes based on ability level. Bear in mind that these are only suggested rest volumes, not absolutes.

Rocker Line: The more rocker line a board has the less its edges and bottom surface are in contact with the water and the turnier the board will be. A less pronounced rocker (where the tail of the board is flatter), means that more of the rails are in contact with the water, so the board goes in a straight line well and is easier to sail upwind. Usually, flat rocker lines are used on boards intended for racing, but the bottom design (double concave, slight V, or flat hull) can contribute to a board’s speed as much as the rocker line.

Generally, a pronounced rocker line indicates that a board is intended for turning more than for going fast. Notable exceptions are wave boards intended for use in big waves: they need to be both turny and fast, as you often need to be quick on big waves. They have what’s called a “fast” rocker line and are often fairly narrow, again for speed.

Advertisement

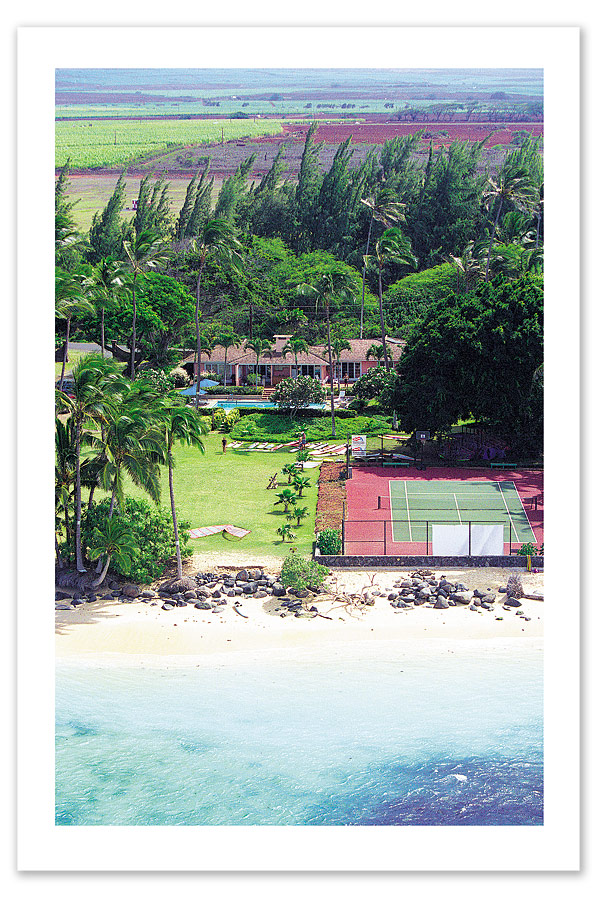

FINS

It was decided before the test began, that boards would be tested with the fins manufacturers provided and intended selling with the boards—and no others. While fin measurements were not verified with the initial board specifications, a few spot checks revealed the fins to be so close to manufacturer’s claims (a mere 2mm difference in some cases) that we include their numbers in the results. Also, in the individual board reviews a fin is considered to have performed well, unless we say otherwise.

The pro testers at the 2000+1 test unanimously agreed that most boards could benefit from having a choice of fins. If a freestyle board is claimed to have incredible range, and our pros agreed that many do indeed, then manufacturers should supply two fins, allowing riders to take full advantage of the board’s design. Some of the RRD Twin Tips and the HiFly Move boards do come supplied with two fins.

Some board makers have returned to a thinner tail design (especially with wave boards), which means that there is little material to actually bolt through for a Powerbox or Tuttle box. This resulted in several boards having bolt heads protruding onto the deck. On larger boards a strong fin box, such as the Powerbox or Tuttle, is warranted due to the extreme force exerted on it by large fins. But the smaller, slashier boards, with their short wave fins, would benefit from using the ubiquitous and adjustable Standard (U.S.) box.

As a general observation, we consider most of the fins, while well designed for their specific use, to be too big. The comment came back time and time again that a fin felt too heavy and took away from the loose nature of many wave boards. However, several guest testers, when faced with dying winds or holes (which too often coincided with approaching waves) commented that they’d prefer bigger fins. Some of the differing opinions between pro and guest testers undoubtedly had to do with sailing ability and experience, though most of our guest testers were excellent sailors.

Andy Gurtner, who oversaw the entire pro test believes it to be a somewhat subjective issue and agrees that some fins make sailing easier even if they are not the ideal fin for the board and conditions. Some people choose to sail larger fins and it’s really a question of performance versus ease of use—something that’s present with all windsurfing gear, not just with fins. It was important throughout the test to acknowledge all guest tester opinions, even when, coming from sailors with differing abilities, they appeared contradictory. With some specialized boards, rider skills became critical. For instance, some designs were so radical—full “banana” rocker lines and Formula race boards—that they were for expert level sailors only.

An extra benefit of owning more fins is that they can actually save you money. With some good quality fins added to your quiver, you can own fewer sails and boards. When experiencing over powered or under powered conditions, simply change the fin and you are back in control. Or, with the adjustable Standard box design, you can reposition the fin to optimize performance (move it back for more speed and forward for improved turning). While this cannot be taken to extremes, it is certainly a less expensive investment and easier alternative than owning an extra board that sees only periodic use. Even if you don’t account for a fin’s rake and leading edge thickness (both of which affect performance), there are some fin characteristics that can easily be explained. A soft tipped fin allows flex and therefore quicker turning ability and looser sliding moves, but it can spin out more (a characteristic that many wave sailors actually want). A stiffer fin can give a rider more confidence in chop as it attaches better, but can be more difficult to reattach when spinning out. Slotted fins (there were none provided with any of this year’s test boards) are thought to reduce spinout, however most spinout problems are usually operator error. Slotted fins really work in whitewater, providing more positive traction. Thruster fins, those small additional fins on this year’s Starboard Starfish for example, also provide extra grip. Interestingly, several boards in the wave and freestyle categories have channels on the bottom intended to act as extra “micro-fins” to add traction.

To be fair, all the fins performed to such a high standard that we admit to being somewhat picky. But, in general we were so impressed that we want the experience of sailing the 2001 gear to be further enhanced any way possible.

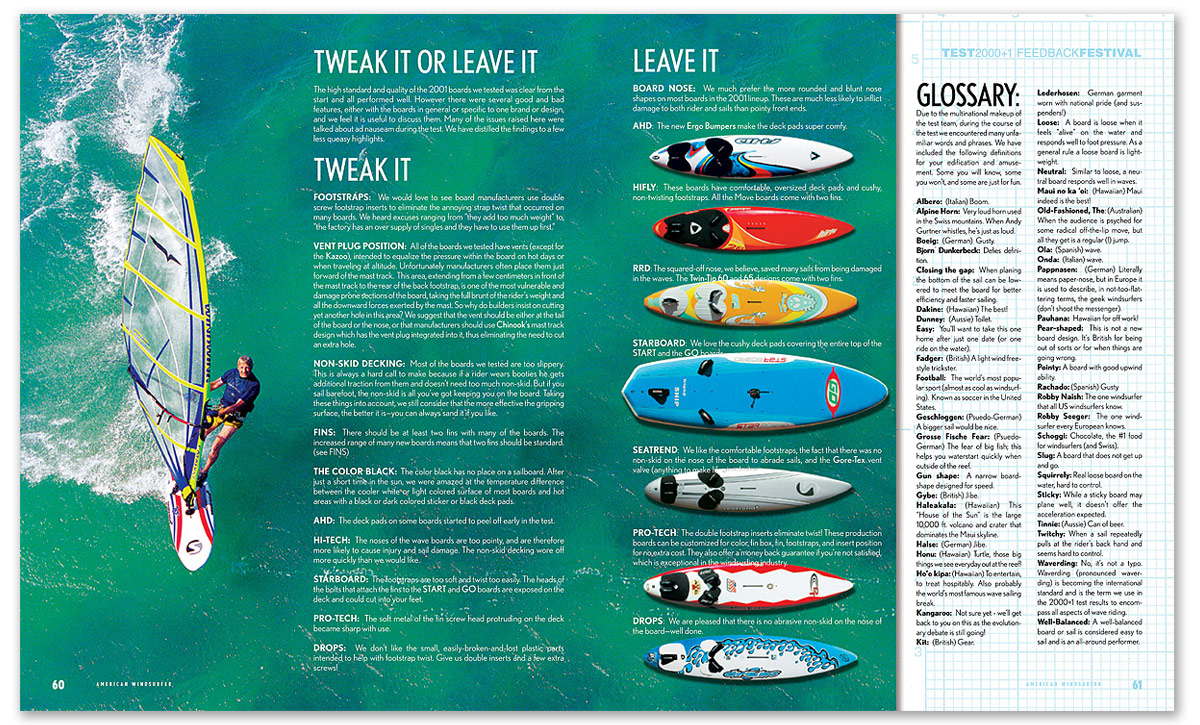

TWEAK IT OR LEAVE IT

The high standard and quality of the 2001 boards we tested was clear from the start and all performed well. However there were several good and bad features, either with the boards in general or specific to one brand or design, and we feel it is useful to discuss them. Many of the issues raised here were talked about ad nauseam during the test. We have distilled the findings to a few less queasy highlights.< (strong>TWEAK IT

Footstraps: We would love to see board manufacturers use double screw footstrap inserts to eliminate the annoying strap twist that occurred on many boards. We heard excuses ranging from “they add too much weight” to, “the factory has an over supply of singles and they have to use them up first.”

Vent Plug Position: All of the boards we tested have vents (except for the Kazoo), intended to equalize the pressure within the board on hot days or when traveling at altitude. Unfortunately manufacturers often place them just forward of the mast track. This area, extending from a few centimeters in front of the mast track to the rear of the back footstrap, is one of the most vulnerable and damage prone sections of the board, taking the full brunt of the rider’s weight and all the downward forces exerted by the mast. So why do builders insist on cutting yet another hole in this area? We suggest that the vent should be either at the tail of the board or the nose, or that manufacturers should use Chinook’s mast track design which has the vent plug integrated into it, thus eliminating the need to cut an extra hole.

Non-Skid Decking: Most of the boards we tested are too slippery. This is always a hard call to make because if a rider wears booties he gets additional traction from them and doesn’t need too much non-skid. But if you sail barefoot, the non-skid is all you’ve got keeping you on the board. Taking these things into account, we still consider that the more effective the gripping surface, the better it is—you can always sand it if you like.

Fins: There should be at least two fins with many of the boards. The increased range of many new boards means that two fins should be standard. (see FINS)

The Color Black: The color black has no place on a sailboard. After just a short time in the sun, we were amazed at the temperature difference between the cooler white or light colored surface of most boards and hot areas with a black or dark colored sticker or black deck pads.

AHD: The deck pads on some boards started to peel off early in the test.

HI-TECH: The noses of the wave boards are too pointy, and are therefore more likely to cause injury and sail damage. The non-skid decking wore off more quickly than we would like.

STARBOARD: The footstraps are too soft and twist too easily. The heads of the bolts that attach the fins to the START and GO boards are exposed on the deck and could cut into your feet.

PRO-TECH: The soft metal of the fin screw head protruding on the deck became sharp with use.

DROPS: We don’t like the small, easily-broken-and-lost plastic parts intended to help with footstrap twist. Give us double inserts and a few extra screws!

LEAVE IT

Board Nose: We much prefer the more rounded and blunt nose shapes on most boards in the 2001 lineup. These are much less likely to inflict damage to both rider and sails than pointy front ends.

AHD: The new Ergo Bumpers make the deck pads super comfy.

HIFLY: These boards have comfortable, oversized deck pads and cushy, non-twisting footstraps. All the Move boards come with two fins.

RRD: The squared-off nose, we believe, saved many sails from being damaged in the waves. The Twin-Tip 60 and 65 designs come with two fins.

STARBOARD: We love the cushy deck pads covering the entire top of the START and the GO boards.

SEATREND: We like the comfortable footstraps, the fact that there was no non-skid on the nose of the board to abrade sails, and the Gore-Tex vent valve (anything to make life simpler).

PRO-TECH: The double footstrap inserts eliminate twist! These production boards can be customized for color, fin box, fin, footstraps, and insert position for no extra cost. They also offer a money back guarantee if you’re not satisfied, which is exceptional in the windsurfing industry.

DROPS: We are pleased that there is no abrasive non-skid on the nose of the board—well done.

GLOSSARY:

Due to the multinational makeup of the test team, during the course of the test we encountered many unfamiliar words and phrases. We have included the following definitions for your edification and amusement. Some you will know, some you won’t, and some are just for fun.

Albero: (Italian) Boom.

Alpine Horn: Very loud horn used in the Swiss mountains. When Andy Gurtner whistles, he’s just as loud.

Boeig: (German) Gusty.

Bjorn Dunkerbeck: Defies definition.

Closing the gap: When planing the bottom of the sail can be lowered to meet the board for better efficiency and faster sailing.

Dakine: (Hawaiian) The best!

Dunney:(Aussie) Toilet.

Easy: You’ll want to take this one home after just one date (or one ride on the water).

Fadger:(British) A light wind freestyle trickster.

Football:The world’s most popular sport (almost as cool as windsurfing) Known as soccer in the United States.

Geschloggen: (Psuedo-German) A bigger sail would be nice.

Grosse Fische Fear: (Psuedo-German) The fear of big fish; this helps you waterstart quickly when outside of the reef.

Gun shape: A narrow board-shape designed for speed.

Gybe: (British) Jibe.

Haleakala: (Hawaiian) This “House of the Sun” is the large 10,000 ft. volcano and crater that dominates the Maui skyline.

Halse: (German) Jibe.

Honu: (Hawaiian) Turtle, those big things we see everyday out at the reef!

Ho’o kipa: (Hawaiian) To entertain, to treat hospitably. Also probably the world’s most famous wave sailing break.

Kangaroo: Not sure yet – we’ll get back to you on this as the evolutionary debate is still going!

Kit: (British) Gear.

Lederhosen: German garment worn with national pride (and suspenders!)

Loose: A board is loose when it feels “alive” on the water and responds well to foot pressure. As a general rule a loose board is lightweight.

Neutral: Similar to loose, a neutral board responds well in waves.

Maui no ka ‘oi:(Hawaiian) Maui indeed is the best!

Old-Fashioned, The: (Australian) When the audience is psyched for some radical off-the-lip move, but all they get is a regular (!) jump.

Ola: (Spanish) wave.

Onda: (Italian) wave.

Pappnasen: (German) Literally means paper-nose, but in Europe it is used to describe, in not-too-flattering terms, the geek windsurfers (don’t shoot the messenger).

Pauhana: Hawaiian for off work!

Pear-shaped: This is not a new board design. It’s British for being out of sorts or for when things are going wrong.

Pointy: A board with good upwind ability.

Rachado: (Spanish) Gusty

Robby Naish: The one windsurfer that all US windsurfers know.

Robby Seeger: The one windsurfer every European knows.

Schoggi: Chocolate, the #1 food for windsurfers (and Swiss).

Slug: A board that does not get up and go.

Squirrely: Real loose board on the water, hard to control.

Sticky: While a sticky board may plane well, it doesn’t offer the acceleration expected.

Tinnie: (Aussie) Can of beer.

Twitchy: When a sail repeatedly pulls at the rider’s back hand and seems hard to control.

Waverding: No, it’s not a typo. Waverding (pronounced waver-ding) is becoming the international standard and is the term we use in the 2000+1 test results to encompass all aspects of wave riding.

Well-Balanced: A well-balanced board or sail is considered easy to sail and is an all-around performer.

Welle: (German) wave.